4th Global

Women’s Empowerment & Leadership Summit

THEME: "Break Barriers, Build Futures"

27-28 Oct 2025

27-28 Oct 2025  Bali, Indonesia

Bali, Indonesia THEME: "Break Barriers, Build Futures"

27-28 Oct 2025

27-28 Oct 2025  Bali, Indonesia

Bali, Indonesia

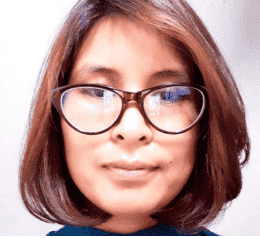

NIWF, Nepal

Title: Incomplete History: The Unheard Voices of Indigenous Women

She is a writer, researcher, and activist focused on the activism and social movements of marginalized communities. As a published author, she has written works such as Nilambit Nibandha, which address issues related to identity, culture, language, politics, indigenous knowledge, and the history of indigenous peoples. She has also contributed to significant projects related to indigenous communities, with a particular emphasis on indigenous women. She has served as a GESI expert, working to address gender and social inclusion through evidence-based policy reform for sustainable conservation. She was the Coordinator for the Tharu Tattoo Convention and the Curator for a mixed media exhibition titled Daule Daule at the Patan Museum. Additionally, she curated the photo exhibition Tharu Way of Knowing and Being at ICIMOD. Through her books and magazine articles, she reflects her unwavering commitment to defending the rights of indigenous communities both in Nepal and globally.

Current situation:

In Nepal, we Indigenous Women continue to be systematically colonized and discriminated by both government and non-government actors. The ongoing loss of our ancestral lands, territories, and resources that are stolen in the name of conservation, eminent domain, and development. Governments frequently establish protected areas, including national parks and conservation areas, often without obtaining our Free Prior and Informed Consent FPIC, which makes us unprotected and vulnerable. For us, land is not just a resource but a sacred, cultural, and spiritual foundation of our distinct identity, and collective ways of life. The fortress model of conservation and militarization criminalizes our traditional knowledge and practices vital to our communities' wellbeing. Indigenous Women living near these areas are frequently arrested, harassed, or fined simply for entering the forest. It must stop.

The land rights struggles, such as the Tharuhat autonomy by the Tharu, save Khokana by the Newa, No Cable Car, No Koshi, and save Mukumlung by the Yakthung (Limbu), and no high voltage transmission station in Bojeni by the Tamang, are for Indigenous sovereignty, self-determination, autonomy, customary self-rule and the protection of sacred lands. Unfortunately, the government responds to our demands with violence, as we saw last week a bullet piercing the chest and thigh of three Indigenous human rights defenders.

Indigenous women face violence, physical assault, rape, harassment, and even imprisonment. We are disproportionately affected by gender-based violence (GBV), compared to non-Indigenous women. Our vulnerability is compounded by multiple layers of oppression and systemic barriers to justice, such as a lack of access to menaingful justice system that permits Indigenous women to speak Indigenous languages in police stations, courts, and government institutions.

The Kamlahari system, a form of bonded labor, officially abolished the practice in 2013, persists in practice. Despite the law, Tharu girls are kept in bondage by political leaders, elites, and authorities who continue to exploit them for domestic labor. Kamlahari girls need justice.

Incomplete History:

Until now, we have been forced to embrace lies in the name of history, where the narratives are often centered around the experiences of men. But we Indigenous Women must not forget that without Indigenous Women’s stories and struggles, the history is incomplete.

Indigenous Women’s Struggles and Resistance:

Too often all we see are photos of young Indigenous Women exhibited as 'beautiful dolls' decorated with cosmetics and jewelry. A grandmother's face full of wrinkles, their cracked heels and calloused palms look more beautiful to me.

Many researchers portray Indigenous Women as enjoying more freedom. “Aadibasi mahila swatantra chhan.” They portray Indigenous Women as strong as Indigenous men or sometimes stronger than men in decision making and in other ways.

In our experience, Indigenous Women's reality is very different from that. I don't see Indigenous Women as free but as persistent. When an outsider sees Indigenous Women working in the fields or going fishing, s/he might assume them free because they are going outside of the house. But the reality is that this is the Indigenous Women's struggle for their life. In the case of decision making, I never saw a woman deciding herself without a husband's permission. My grandmother once said, “Shriman lai na sodhera maaita pani jana sakdaina, mahila.” An Indigenous Woman can not even visit her “Maita”, her parents’ house, without asking her husband.

Grandmothers learning:

The grandmothers don't know how to read. Again, they possess diverse form of knowledge and skills, beyond formal education. Traditional knowledge passed down through generations, such as the skills grandmothers have in fishing, weaving, pottery, farming, and survival, is invaluable and unique.

Is knowledge only available at the school? Is learning solely determined by a certificate? No. Our grandmothers had a distinct method of learning.Their knowledge was women from a variety of sources, including the kitchen, rivers, forests, fields, and the wisdom of ancestors.